It’s a good time for tea. It’s everywhere. A recent survey showed half of all Brits drink it more than water. And for hundreds of years Britain has literally run on the stuff. But how much do we really know about our favourite drink? Most of us only associate ‘tea’ with a little white mesh bag we pull from a box and unceremoniously dunk in hot water. Ask about the plant it comes from, what a ‘flush’ is or a leaf grade like ‘Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe’ and you’re likely to be met with a blank look.

To answer these questions I’m in Sri Lanka, home of perhaps the finest tea gardens in the world. Still best known by the colonial name for the island, ‘Ceylon Tea’ remains a vital ingredient in many everyday English breakfast blends, bringing a vital mellow aroma and flavour to balance other bolder-tasting teas in the mix, usually from India or Africa.

But come here, away from the world of mass-produced tea bags, you soon discover another side completely to this plant. In fact, Sri Lanka produces some of the finest teas you can possibly grace a cup with. Once you get your nose in there’s a wealth of craft, tradition, aroma and flavour waiting to be appreciated that makes the art of producing tea far closer to that of fine wines or whiskies. And the obvious place to start is in Sri Lanka’s famous tea fields themselves.

“It’s not much further,” announces the ever-cheerful Ishanda. He is my companion on the hike up through the stunning tea plantations that surround Nuwara Eliya in Sri Lanka’s famous ‘Hill Country’. Ishanda is something of a local expert. A naturalist and guide from the nearby Jetwing St Andrew’s hotel, he is putting his considerable knowledge to good use this morning.

We’ve only been walking twenty minutes and already we’ve covered the entire history of tea, the science of the ‘cloud forests’ that surround this area and a whistle-stop tour of the striking local flora and fauna. This includes the several bird species that have flown by us in a riot of colour. Then he stops and draws my attention to one plant in particular.

“Here,” he says. “Camellia sinensis. Tea. There are some different cultivars, but all tea is made from this one plant.”

It’s strange to think that the humble evergreen shrub before me has literally shaped the social and political landscape of the world for centuries. I lean closer and inspect the bright green buds at the top then gaze past the plant, down the valley over the many hundreds and thousands of bushes blooming below. It’s almost more than the eye, and the mind, can take in.

“Come on.” He says. “There are better views up ahead.”

Our destination is ‘Lover’s Leap’, a waterfall fed by streams crashing down from Piduruthalagala, Sri Lanka’s highest mountain. Taking another breather halfway up, we’re suddenly standing on a viewpoint completely surrounded by tea fields. Emerald rows are dotted with tea puckers. Each is busy with the careful yet physically demanding work of pulling off the top leaves and filling the sacks on their backs, which are carried via a band across the forehead.

The view is spectacular. Mist creeps over the horizon and light catches a Hindu temple at the foot of the hill. Like so many views in Sri Lanka, it has all the qualities of an old master painting. It’s also a view that hasn’t changed much since this estate’s first owner set up shop in 1867.

Now part of the Pedro Estate, Lover’s Leap is special because the Sri Lankan tea pioneer James Taylor originally owned it. Taylor was a hardy Scotsman who started work on the Sri Lankan coffee plantations that pre-dated tea here, before cutting his teeth in the more established British-colonial tea fields of India. Tea was already huge business for the British with the East India Company trading first from China, then India. Following his return to Sri Lanka, Taylor almost single handily started what is now a multi-billion dollar industry and this island’s most famous export. Tea had already been cultivated on the island and run as a trial in the Botanical Gardens at Peradeniya. However, it was Taylor who started planting it on Kandy’s Loolecondera Coffee Estate in 1867.

Starting with 200 plants, the first export to the London Tea Exchange in 1875 was just 23 pounds in weight. But by 1890 that has bloomed to 22,900 tonnes. To get grow to that point, Taylor worked with fellow countryman, the Scottish millionaire Sir Thomas ‘Tommy’ Lipton. Lipton is now a household name for tea but at the time he was an entrepreneur who ran a successful chain of grocers across Scotland. He entered the tea market with the intention of lowering prices, believing tea should be for everyone and not the preserve of high society. A chance meeting with Taylor lead to him investing heavily in Ceylon tea, contributing to its rapid expansion and global reputation.

Back on the trail we turn a final corner to see the spectacular waterfall, pouring white from the hill. A husband and wife from the local village emerge out of the misty cloud forest laden with a huge bundle of firewood on their heads before fading away again like ghosts. As the waterfall crashes around us, and I pose for a picture, Ishanda tells me that the name Lover’s Leap comes from an ancient legend. Apparently two star-crossed lovers are said to have jumped to their deaths here rather than be without one another, much like a Sri Lankan Romeo and Juliet.

I don’t know if it’s the spectral villagers, Ishanda’s romantic tales or a slight lack of oxygen from the altitude but the place takes on a slight Gothic quality – in the best Victorian tradition, of course. Somewhat implausibly, a lone tuk-tuk is waiting at the top, having just dropped off some other waterfall visitors, and we hop in for the ride back down to the main estate and tea factory.

There we meet Kalaivani, the estate’s guide. After watching the pluckers at work from a beauty spot, it’s time for me to get my hands dirty. Kalaivani leads us into the fields that surround the factory and demonstrates how just the top two leaves and the bud of the tea plant must be taken. I have a go and fail. It takes skill and dexterity to grasp exactly the right bits between thumb and forefinger. Let alone to do it at speed. Having witnessed first-hand the sort of terrain where thousands of pluckers work gruelling eight-hour shifts, I was already in awe of the stamina required for this job. This little lesson makes it clear there is much more to it than physical staying-power.

I ask Kalaivani what it’s like for the women in the fields. “I come from a family of tea pluckers,” she says. “My mother was a tea plucker. My father works here in the factory. It’s hard work, but the conditions here are great.”

This is good to hear as other estates on the island are known for being less impressive, which led to many workers taking industrial action back in 2006. I ask if the women have a secret to getting through the day. Kalaivani laughs: “I think the whole factory runs on tea! I must have five or six cups a day minimum. We all love tea!”

A visit to THE tea factory

We cross the courtyard and are led through the doors into one of the weather-beaten corrugated buildings in the heart of the factory. The first thing to hit me is the heat. Huge dryers used for drying the tea are kicking out some serious warm air. Hill Country may be cooler than much of Sri Lanka because of its altitude, but this is one warm workplace. The other thing I can’t help but notice is the pungent, all-encompassing perfume of tea. It is at once familiar and unfamiliar as the leaves go through various stages of production. But seeing tea’s processes laid out like this reveals exactly how labour-intensive and highly scientific it is. Food for thought next time I’m putting the kettle on.

To make sense of it all we take a guided tour through the series of rooms that house the different stages of tea production. First comes ‘withering’ on temperature-controlled racks. This reduces about 30% of the moisture from the fresh green leaves we plucked outside. Then there is the ‘disruption’ or maceration process, which lightly bruises or tears the leaves in large mechanised trays or baskets. This breaks down structures in the leaf and starts the all important oxidation process. Oxidation proper, also known as ‘fermentation’ comes next. Leaves are left in a room to darken and dry. This is a very carefully timed process because it is when the chlorophyll is broken down and tannins are released. And it is the tannins that give the tea many of its complex taste and aroma compounds. Next, heat-induced ‘fixation’ stops the oxidisation process with a blast of warmth and the leaves are rolled or ‘shaped’ and dried one last time.

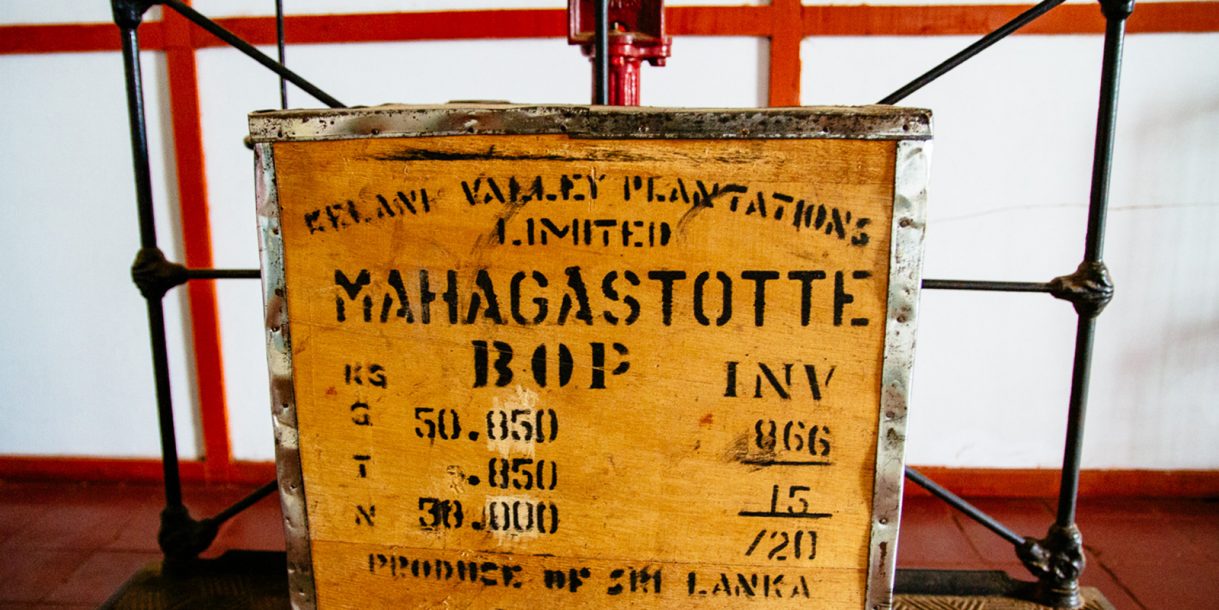

At this point the tea gets graded by sifting it through different sizes of mesh. The classifications are many and complicated but the long and undamaged leaves of ‘Orange Pekoe’ are firmly the top of the class. It is followed by BOP or ‘Broken Orange Pekoe’ – a slightly more broken version of the same. Further down the scale you move through ‘Fannings’ – smaller particles still – all the way to ‘Dust’. These are dark, fine particles that are of a much lower quality and are only used in tea bags.

We duck out of the heat of the factory to drink in the cool mountain air on a terrace overlooking the fields. And hopefully some of the good stuff too. Thankfully Kalaivani appears with cups containing liquid of the most beautiful golden amber hue. This is Lover’s Leap tea or ‘The Champagne of Teas’, according to the estate. It’s a fair nickname though and well-earned; the tea is one of the finest in the country. Delicate, fragrant and bright and fresh on the palate, it is drunk without milk and so delicious that it had pride of place as the tea served at the Queen’s Jubilee in 2012.

So what makes it so fine, I wonder. “It’s the altitude and climate,” replies Kalaivani. “We are 6000 feet above sea level.”

She explains that just like its Champagne namesake in the wine world, the conditions mean the plant’s natural flavours aren’t baked or over-amplified by the sun. In fact the finest teas here are picked in the first ‘flush’, the season from January to March when the weather is cooler and drier. Suitably refreshed I thank her and buy a few packets of this spectacular tea to take home.

A short ride takes me into Nuwara Eliya town, a charming mix of fading colonial grandeur and colourful hustle and bustle. We pass a famous red-brick post office that could be air-lifted from any Victorian market town in the UK. It’s not just tea that brings the British here. The architecture is extraordinary and one of its many highlights has to be Jetwing St Andrew’s hotel. As the name suggests the building was originally a favourite among Scottish planters with a passion for golf. And today it remains a beautifully grand old colonial affair, complete with original billiard room and a lovely conservatory that is perfect for a spot afternoon tea.

Over traditional tea and cakes I meet Jetwing St Andrew’s resident ‘tea sommelier’. He guides me expertly through teas from this and other areas of the island. Although Nuwara Eliya’s teas are among the best, it turns out that teas from neighbouring Kandy are also prized as a ‘mid-grown’ product from slightly lower altitudes with more intensity of flavour. Also mid-grown are teas from the ‘Uva’ region, where more extreme weather conditions create a more powerfully aromatic tea.

Indeed all Sri Lanka’s regions are now protected like ‘appellations’ in wine. And all have very different micro-climates. The final subset are ‘low-grown’ teas from further south. There tea is planted on vast coastal plains, growing quicker due to the wetter conditions and resulting in the darkest and strongest teas you can find here. I try Jetwing St Andrew’s house-blended breakfast made with a blend of mostly local teas, as well as its green tea and much-prized silver-tipped tea from Imbulpitiya, one of the few white teas produced outside China. All are absolutely delicious. If Lover’s Leap is the Champagne, these are perhaps the ‘Claret’, ‘Vine Verde’ and ‘Riesling’.

After dinner in the hotel’s dining room under its original panel-beaten ceiling, I end the day with a surreal but brilliant experience. As darkness falls, I meet my old friend Ishanda out in the garden. We strap on head-torches and he leads me through the Jetwing St Andrew’s hotel kitchen garden, bursting with vegetables, and up into a mini wetlands reserve he’s created on-site.

What follows is a fascinating frog-watching tour that reveals the many rare and interesting species that call this little sanctuary home. Apparently the climate in Nuwara Eliya isn’t just good for tea. Frogs think this place is paradise too. We lift leaves and study branches to find a range of exotic creatures of all shapes and sizes, including one frog no bigger than my fingernail. Serenaded by their burbling choruses, we make our way back to the hotel for a last nightcap by the fire.

The next day I’m up early for the short transfer by car to somewhere truly special. Heading up a winding mountain road through more lush, green tea terraces, the views grow more and more spectacular. And vertiginous. Then we’re turning into an even steeper private driveway that lifts us up past tea pluckers and groups of waving children until delivering me at a perfectly preserved nineteenth-century Scottish planter’s bungalow – Jetwing Warwick Gardens.

I doubt anywhere on the entire island is more deserving of the label ‘hidden gem’. Bought by Jetwing in 2002 as a derelict but largely unchanged property, Jetwing Warwick Gardens was painstakingly restored to its former glory over a seven-year period. To walk through the doors of this luxury villa now is to walk back in time. You truly experience what life must have been like in this house for the British planters who called these breathtaking hills home all those years ago.

Everything remains, from the original Aga cooker to the kitchen garden that provides the hotel with produce for its delicious rice and curry dishes. What wasn’t left behind has been sympathetically replaced with period hardwood furniture ranging from the classic and beautiful leather-bound desk in the office to an old baby grand piano positioned to give its players views out over the terrace.

I spend the afternoon leisurely exploring the gardens and the local trails through the tea bushes. Then I take the chance to sit down with the hotel manager, Faris, for – what else – a cup of tea. They grow their own here, along with their own coffee, and it is a deeper, slightly more ‘mid-grown’ cup. More intense but no less delicious. I take a long sip and stretch back, looking over the pretty flower beds and the lawn.

Faris loves it here, and it’s easy to see why. As well as being the manager, he has extensive experience in the tea industry and is something of a naturalist in his (now very) spare time. We run through some of the 40-odd species of birds that live here as the first flushes of sunset fire the sides of the sheer-sided valley below. It’s blissful; so quiet you could hear a pin drop. The perfect final stop after a busy few days exploring tea country and getting a taste of this remarkable plant.

As darkness starts to fall I’m handed a cold gin and tonic and asked which of the many vegetables from the garden I’d like in this evening’s dinner. Now that’s my kind of service. I quietly make plans to return here and stay in this spot for a very long time.